According to a worldwide survey by the social-networking platform ‘Badoo’ from 2011, Germans are the world’s least funny nation whereas US-Americans are seen as the world’s most comic nation – come on guys, are you serious? Call me biased, but as a German, I can’t help wondering where that result came from. I guess we all watched too many sitcoms when we were growing up, such as ‘The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air’ and ‘Friends’ and are therefore simply used to the American way of funny. According to my research, only a few German TV shows were ever shown abroad, among them ‘Die Schwarzwaldklinik’ (Black Forest Clinic) – a huge international success during the late 1980s, being sold to 28 countries, but it was a drama series and certainly not fun.

So, does this mean the world just doesn’t know German humour and therefore, has no clue about it? Let’s take a look back through history which may help us understand.

Christianity spread in Germany between the 4th and the 11th centuries. Believe it or not, laughing was seriously seen as something suspicious and pagan during this period. The church fought against laughing, as they viewed a simple laugh as a devilish thing. They reminded people that in the entire bible there is not one single reference to Jesus laughing (what a party pooper he must have been!) and therefore, laughing was forbidden inside monasteries.

However, of all places, it was monasteries, with their scribes, that started collecting jokes in early medieval times, whereas a simple farmer living in the 13th or 14th century wouldn’t have understood a joke as such. The laughing culture of a village came from Carnival, and Carnival is not based on jokes but on grotesque humour with its origins in pagan, rural culture. People celebrated as they were overjoyed, having survived wintertime. However, Carnival was another cult and officially condemned by the church.

Again it was monks who, celebrating church services, dressed pigs up in priest’s cassocks at Easter time to celebrate the end of the fasting period. Many church traditions originated from ancient, non-Christian rituals and perhaps some ironic, satirical esprit.

This type of celebration might have resembled a modern Carnival in some ways. Just think of the huge, bizarre dolls portraying politicians during Carnival parades today.

A typical German comic book, ‘Till Eulenspiegel’, considered the most important work of medieval times, was written between the 13th and 15th centuries. It doesn’t have any jokes, but it shows the national humour that was common in Germany at that time.

Until the 18th century, jesters continued to amuse the noble society at court. However, this kind of amusement was met with criticism from the Proponents of Enlightenment, and the newly emerging bourgeoisie. They drew a picture of this court life believing that superficial merriment reigned there, not merriment that came from the heart; making fun of others was criticized.

In the 19th century, traditional society, based on land ownership, transformed into industrialization. Humour allowed people to express their resentment and established a sense of community, as shared laughter was often more important than the content of a joke or caricature. Humour kept people’s political consciousness alive, as Europeans were in the process of leaving absolutist society behind and moving towards a society in which they had more influence.

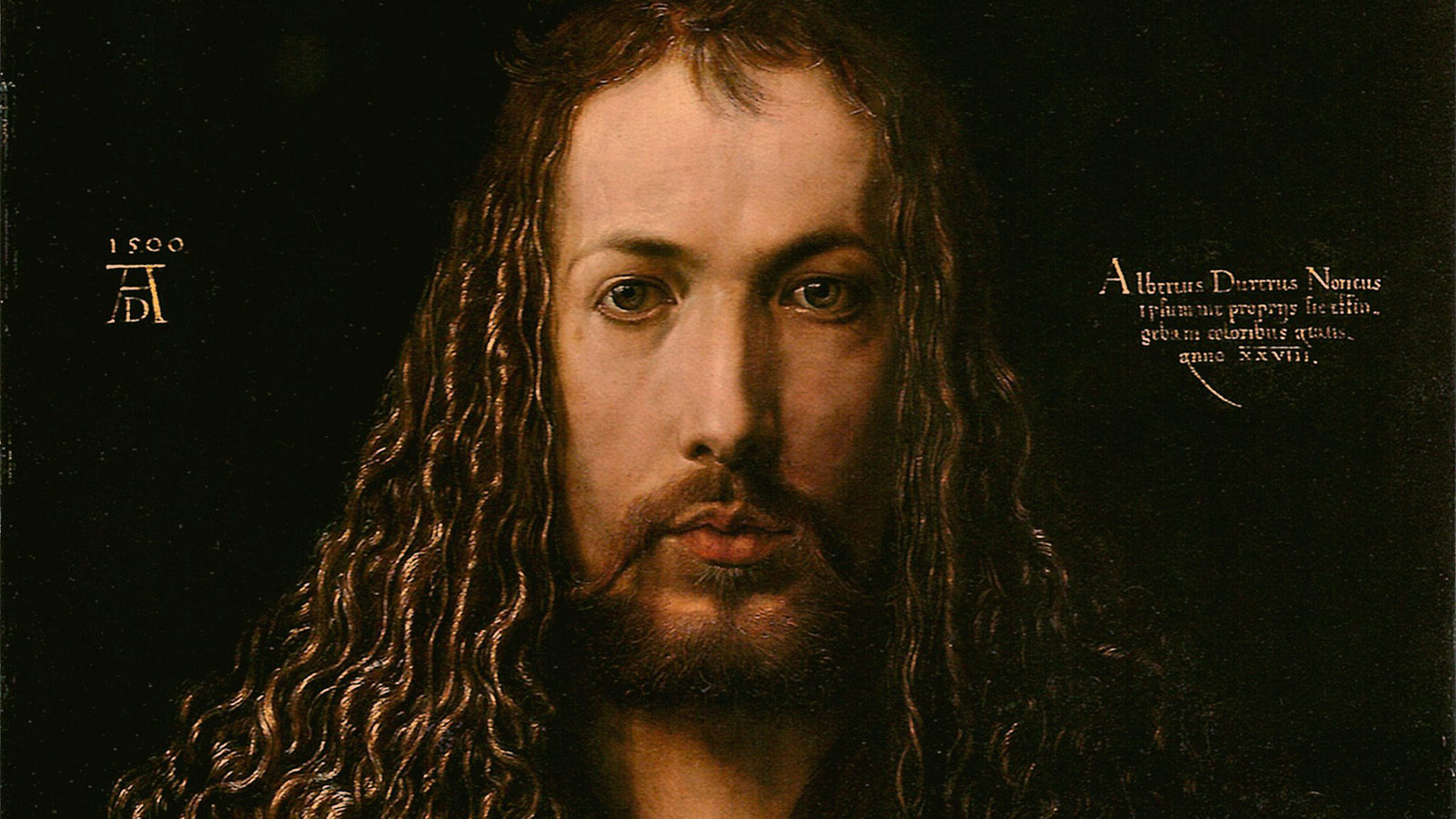

In the 1920s, revue operetta, in which nonsense, criticism, and jazz merged, experienced its peak. In 1928, Mischa Spoliansky’s, ‘Es liegt in der Luft’ (It’s in the air) celebrated its premiere at Kurfürstendamm in Berlin. Marlene Dietrich was discovered when performing that play. Among other songs, she sang a song about a ménage à trois, accompanied by Margo Lion and Oskar Karlweis. ‘Wenn die beste Freundin (When the best friend) plays out a whole new understanding of sexuality and gender roles, ironically but seriously.

Marlene Dietrich & Margo Lion – Wenn die beste Freundin (1931) – YouTube

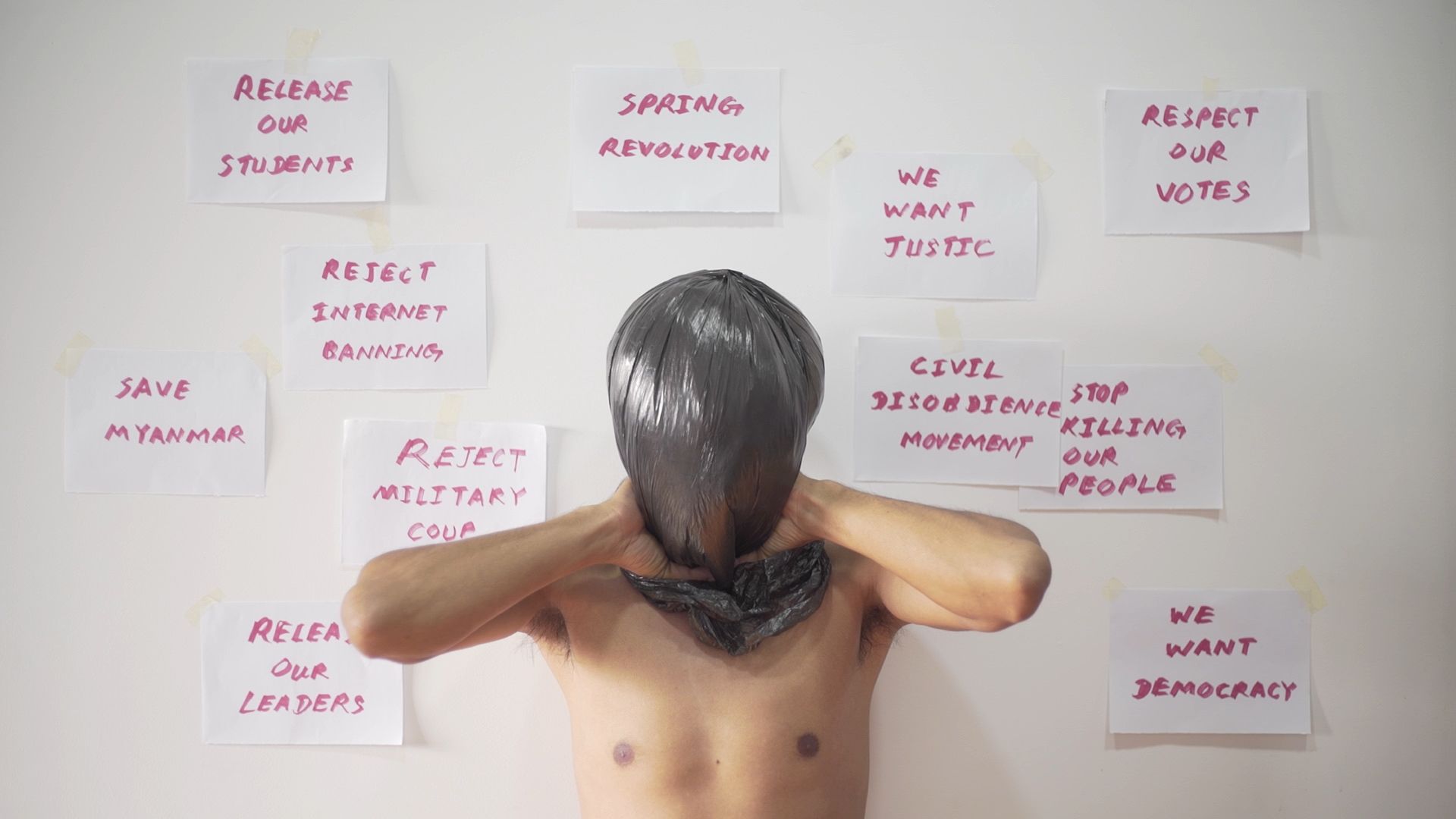

Much like monks dressed a pig in a priest’s costume, carnival became a way for the working class to mock their political leaders and express criticism. When the Nazis came to power in Germany, they saw carnival as another vehicle to infuse their ideology into people’s lives. They encouraged more organised parades, introduced the Prince’s Proclamation and discouraged the more anarchic aspects. Mockery of their political leaders was disallowed, jokes were made at the expense of Jews, the French, Russians and The League of Nations. Crossdressing was abandoned to favour the Nazis fear of homosexuality. In rare instances where people did dare to mock the Nazi regime, such as Karl Küppner, who stretched out his arm in a Hitler salute whilst commenting, “Looks like rain,” they were put in jail. Another, Leo Statz, president of Düsseldorf’s Carnival committee, who repeatedly annoyed the regime, was executed.

Let’s step a few decades forward and take a look at Heinz Erhardt, a famous comedian during the 1950s and 1960s. His humour is built primarily on wordplay and twisted idioms. Many of his poems deal with futility, transience and death, therefore they can be seen as black humour. His performances often included piano playing, singing and dancing. The following video shows a short scene out of his movie, ‘Das kann doch unseren Willi nicht erschüttern.’ (This can’t unsettle Willi). The film is regarded as a mix between comedy and satire, as two neighbouring families constantly compete against each other.

Heinz Erhardt – Immer wenn ich traurig bin | Das kann doch unsren Willi nicht erschüttern – YouTube

And last but not least, let’s take a look at Jan Böhmermann, who became a household name a couple of years ago when making fun of Turkey’s president Erdoğan. Cheeky Mr. Böhmermann read out a poem during his show, using profane language. As a result, the Turkish government demanded that the German government pursue criminal prosecution against the comedian. Chancellor Angela Merkel apologized for Böhmermann’s “intentionally hurtful” poem – which she later called “a mistake”. However, Merkel announced in a press conference that the German government had approved Böhmermann’s criminal prosecution. Intense criticism followed the Chancellor’s decision, including speculation that she decided to allow the prosecution in order to protect Germany’s refugee deal with Turkey. The case was dropped in October 2016.

Let’s let Böhmermann have the final say about German humour: “In Germany, we’re allowed to say anything–as long as we don’t use irony or humour.”